Women who have ovarian tissue removed and then transplanted back in them at a later date have a good chance of falling pregnant, a study has found.

Those women who put their fertility “on ice” because of cancer also have little risk of the disease coming back as a result of the transplanted tissue.

The research, published in the journal Human Reproduction, found that transplanted ovarian tissue can last at least 10 years in some cases, giving women several chances to bear children.

The successful treatment could pave the way for fertility to be restored in many more women who, until now, have been unable to have babies due to the harsh effects of some medical treatments.

In the latest analysis, experts reviewed 41 Danish women who had a total of 53 transplants of thawed ovarian tissue, and who were followed for a decade.

The average age when tissue was frozen was 29.8 years. Out of the 41 women, 32 wished to become pregnant. Ten (31 per cent) were successful and had at least one child.

Overall, 14 children were born to the 41 women – eight naturally and six through IVF.

There were also two abortions during the study – one because the woman was separating from her partner and the other because of recurrent breast cancer.

A third woman experienced a miscarriage at 19 weeks.

Dr Annette Jensen, from the Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark, who worked on the study, said preserving fertility has increasingly become part of the treatment plan for young cancer patients.

Overall, almost 800 women have had ovarian tissue frozen as part of a programme started in Denmark in 2000.

Dr Jensen said: “As far as we know, this is the largest series of ovarian tissue transplantation performed worldwide, and these findings show that grafted ovarian tissue is effective in restoring ovarian function in a safe manner.

“The fact that cancer survivors are now able to have a child of their own is an immense quality-of-life boost tor them.”

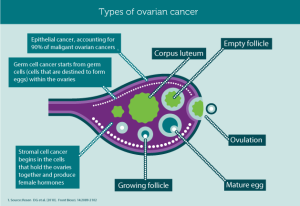

Three of the 41 women in the study had their cancer return. Two of them had breast cancer at the site of their original tumours, while a Ewing’s sarcoma patient suffered a relapse.

The researchers said none of the recurrences appeared to be related to the transplants.

Dr Jensen said: “It’s important that women who have received transplanted ovarian tissue continue to be followed up.

“In particular, we have not performed transplants in patients who have suffered from leukaemia, since the ovarian tissue may harbour malignant cells in this group of patients.”

Dr Jensen said she hoped the study would “enable this procedure to be regarded as an established method in other parts of the world”.